Wealth & Poverty Review Why Joe Biden’s Tax Plan Isn’t Going To Work

Originally published at New World EconomicsI was interviewed recently by a somewhat Left-leaning outlet, and the question came up: Why don’t we “tax all income the same”? In other words, shouldn’t we tax dividends, interest and capital gains at the same (high) rates as the regular income tax? This question has been around forever, but it is particularly pertinent now that President Joe Biden has released a budget proposal that indeed taxes capital gains at potentially the highest rate of income tax, presently 39.6%. This is about double the current capital gains tax on long-term holdings, of 20%.

Biden is not the first one to try this. Republican president Richard Nixon did something similar in 1969, which contributed to the disastrous economic outcome of the 1970s. Congress, realizing its error (despite its Democrat majority at the time), returned rates to their pre-Nixon levels in 1978. A tax reform in 1986 reduced the top Federal income tax rate to 28%; and, perhaps to gain Democrat support, also raised the capital gains tax to 28%. But, these rates again diverged soon afterwards. Indeed, this has been tried again and again in developed countries since at least the 1920s, and has also been abandoned again and again, such that this supposed principle of “taxing all income the same” exists nowhere today.

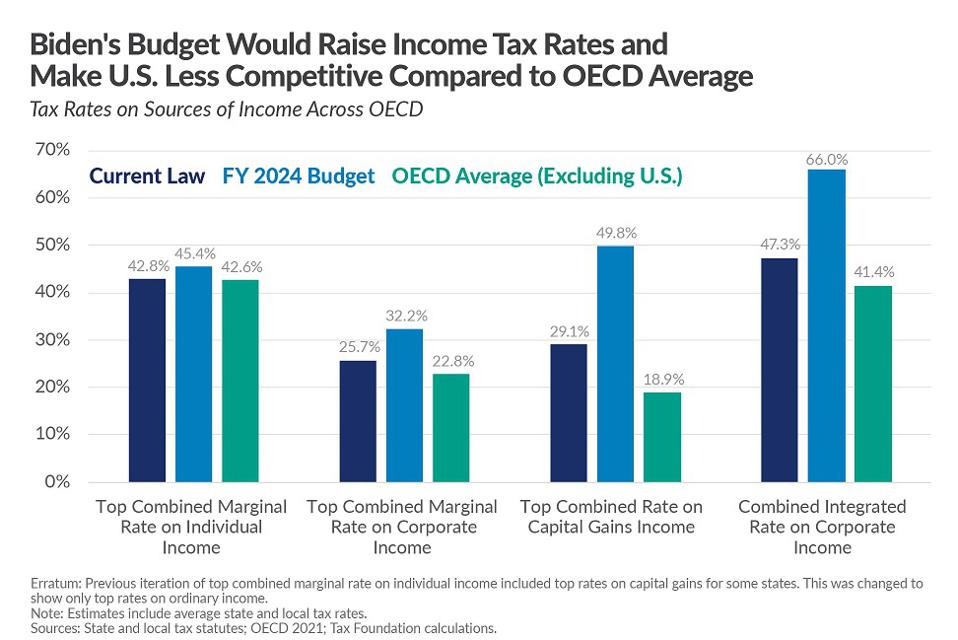

It is one of those things — like state communism — that might sound nice on paper, but doesn’t work in the real world. Today, high-tax Europe has low taxes on capital — lower rates on corporate income, dividends, interest and capital gains, than the US. That is one reason why Europe’s economies are somewhat healthier than one might expect, given their very high tax burdens (tax/GDP ratio). For many years, some of the most successful countries didn’t tax capital gains (on equities) at all, including: Germany, Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Basically, the effects of high taxes on capital are very, very bad, and lead to a very bad economy. In comparison, taxes on consumption, such as a retail sales tax or VAT, can generate high amounts of revenue with relatively modest negative economic effects. When you have a bad economy, several things happen: there are a lot of unemployed and others in financial difficulty. This creates a lot of pressure on governments to spend more on socialistic programs. Also, people without jobs, and struggling businesses, do not pay much taxes. Tax revenue is depressed. Thus, a government has a lot of problems and expenses, and not a lot of revenue. These governments either fix their problems, or they collapse into disorder. Mostly, they fix their problems, eventually, which is why (as I mentioned) there are no governments today that tax capital at the same rates as regular income.

The regular tax on capital is the corporate income tax. Warren Buffet is regularly found near the top of lists of wealthy Americans. But, he didn’t get there because of his high salary at Berkshire Hathaway, or (realized) capital gains. Buffett himself admits that he doesn’t pay much in Federal individual income taxes, compared to his great wealth. He is there because he owns 16.45% of Berkshire Hathaway. In 2019, Berkshire Hathaway paid $3.6 billion in taxes. Buffett’s share was $592 million in taxes, paid indirectly. And that was just one year.

Imagine a small business, like an automobile dealership, that is 100% owned by the founder. This company made $2 million in profit (income), paid $500,000 in taxes, and left the rest of the profit in a corporate bank account, distributing nothing to the 100% owner. Is anyone going to claim that the owner “paid no taxes”? Or that the $1.5 million in company profit was not, indirectly, the profit (income) of the owner? How is it any different for Warren Buffett?

After being taxed at the corporate level, this income can be double-taxed as dividend income. This makes no sense, and in fact leads to well-known financial distortions (basically, companies use increased debt and share buybacks as a lower-tax alternative). Corporate income should be taxed at the corporate level, and tax-free on distribution. Interest income is tax-free (categorized as an expense) at the corporate level, and then taxed on the individual level. This also leads to distortions (a tendency toward too much debt since it is tax-free for corporations). Corporate profits paid as interest should be taxed at the corporate level, and tax-free afterwards.

What about capital gains? Capital gains are not really “income” arising from business. It is just trading of assets. In effect, it is a type of wealth tax, not an income tax. Much of the “capital gain” can be inflationary. Today, a person might retire, and sell a house in California for $850,000 that they bought in 1967 for $35,000. Was that really a capital gain? Or just inflation? If they were to buy a house again, in the same neighborhood, it would cost them $850,000. It is just a house-price of money. (This is why property is often exempt from capital gains taxes.) But is it any different for stocks, or art? In practice, the value of a security reflects expectations of future cashflows; or, profits. Those profits will be taxed, under the regular corporate income tax. In practical terms, capital gains taxes become horrifically complicated. Probably more than half of the 70,000 pages of the US tax code have to do with capital gains taxes. It is the only tax that is not resolved in a single year timeframe. Profit, dividends, or interest income is all calculated for the prior calendar year. But for capital gains, you have transactions spanning sometimes decades.

In practical terms, capital gains taxes are one of the most destructive and unnecessary taxes. The amount of economic damage they cause is all out of proportion to their revenue. Also, as we see, capital is already taxed at the corporate level, and does not need to be taxed again as “capital gain.” From either a practical or theoretical standpoint, capital gains taxes should be eliminated; which is why the earlier list of countries that didn’t tax capital gains in the past is also a list of countries with better-than-average economic performance. (Japan started to tax capital gains in 1989.) A strong economy leads to higher tax revenues, from all other sources. Thus, eliminating capital gains taxes leads to more revenue, not less. (I look into these patterns, with a lot of real-life examples, in my 2019 book The Magic Formula.)

Today, there are some cases where regular corporate operating income is classified as “capital gains” to get a lower tax rate. This includes investment managers, whose fees are regular operating income by any definition. Some agitation to “tax capital gains the same as regular income” represents irritation at this convoluted arrangement. Operating income of investment managers should be taxed at regular corporate rates. However, these corporate rates should also be low, or investment managers will probably relocate to countries that offer a better deal. This is already true of employee stock options, which appear to be a type of capital gain, but are taxed as regular employment income today.

We have run this experiment many, many times. In the 1920s, socialists in Britain argued that income from capital should not only be taxed at the same rate as employment income, but that “unearned income” should actually have a surtax! The result was that the British economy — during the 19th century one of the best in the world — was, during the 20th century, one of the worst. Britain had been the wealthiest country in the world, but in 1970, per-capita GDP was less than half of the US. Britain didn’t start to recover until … Margaret Thatcher got rid of the “unearned income” surtax in 1979, and then lowered taxes on capital still further.

If you think you are going to do the same thing today, but get a different result, I tell you that this will not happen. Socialists always have all kinds of fantasies, but they live in the same real world as the rest of us, and in the real world there are certain cause and effect relationships that are, by now, well known.